Secret of Binary ELF

What is Executable and Linkable Format ELF?

Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) is a standard file format designed for executable files, object code, shared libraries and core dumps. This format was adopted especially for UNIX operating systems. ELF file is an extremely flexible format for representing binary code in a system, following the ELF standard you can represent a kernel binary just as easily as a normal executable or a system library.

Kernel is the main component of a Linux Operating System (OS) and is the core interface between a computer’s hardware and process. (You can compare Kernel to a human heart)

ELF format is in use by several different operating systems like:

- OpenBSD

- QNX

- Fuchsia

- Debian

- Ubuntu and more.

The specification does not clarify the filename extension for the ELF file. Exist a variety of letter combinations as: .axf, .bin, .elf, .o, .prx, .puff, .ko, .so, and .mod, or none.

Before understanding the Structure of an ELF binary let’s try to understand what is the “Object Code and Shared Libraries”.

What is Object Code or Machine Code?

Object Code is the output of a compiler after the source code is compiled. The Object Code is also called Machine Code. This instruction can be understood directly by the CPU (Central Processing Unit). Sometimes, like a human, the Computer has its own language. To execute the instruction the computer needs to know how to do that, for this Object Code is made.

Example of the source code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#include <stdio.h>

int main(){

printf("Secret of the ELF Binary!\n");

return 0;

}

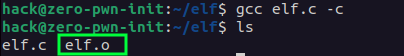

The basic command for compiling a file containing an Object File is “gcc”. You specify the -c argument to tell gcc to compile, but not link, the file. The result of a successful compilation is an object file, which has the same name as the source file but an extension of .o.

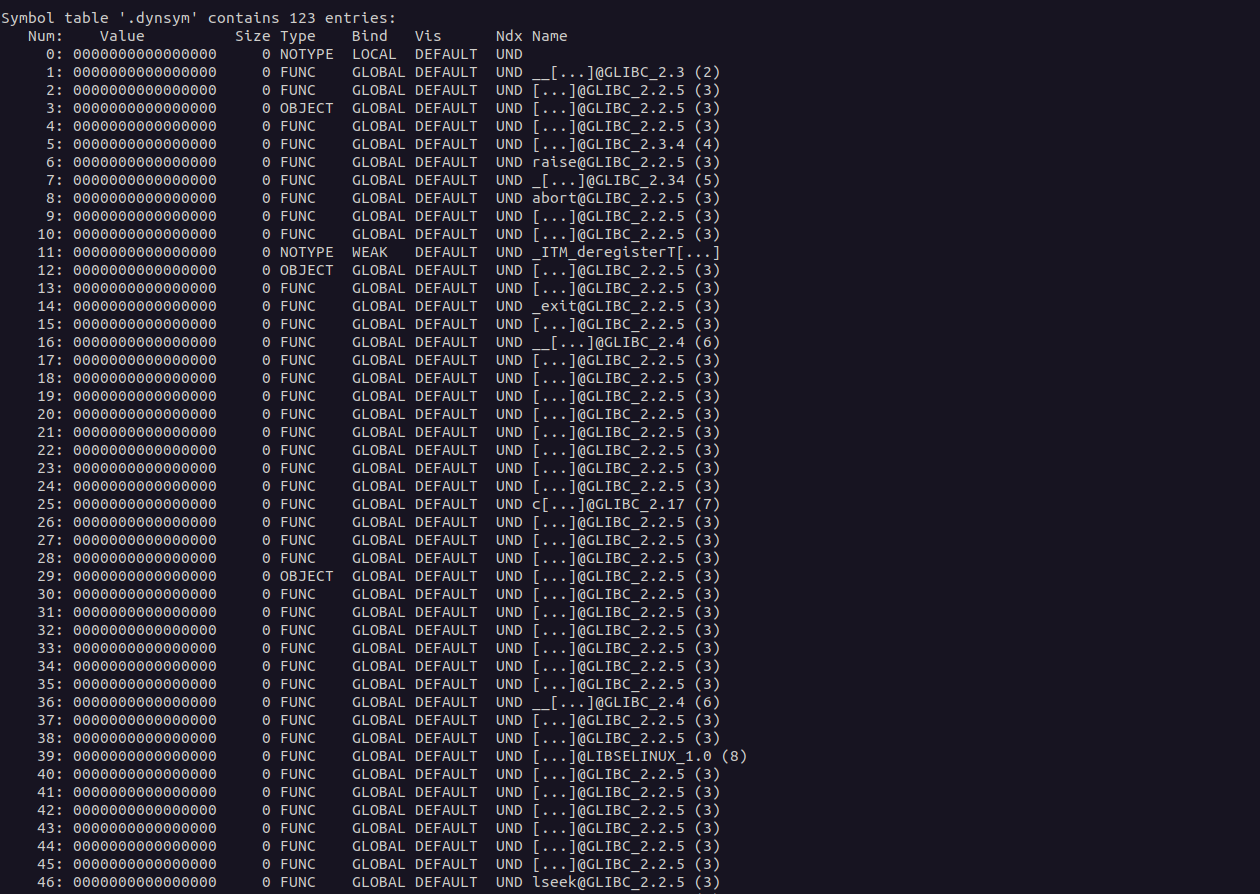

Using objdump we can display the disassembled code of the .o file, showing both the hexadecimal machine code and the corresponding assembly instructions.

What is a Shared Library File?

Shared Libraries are libraries that can be linked to by any program during run-time. They enable the use of code that can be loaded from any location in the memory segment. The shared library code, once loaded, can be used by any number of programs. As a result, because a lot of code is kept common in the form of a shared library, program size and memory footprint can be kept low.

Note: Memory segmentation is a technique of the operating system to manage memory into segments and sections. Segmentation is a reference to a memory location that includes a value that identifies a segment and an offset (memory location) within that segment.

Because the library code can be changed, modified, and recompiled without having to recompile the applications that use this library, shared libraries provide modularity to the development environment. A shared library can be accessed by a different name:

Name used by linker lib followed by the library name and followed by the extension .so (Exemple: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so)

Fully qualified name or “so” name (Example: /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6)

The Standard location to find this library is:

- /lib

- /usr/lib

- /usr/local/lib

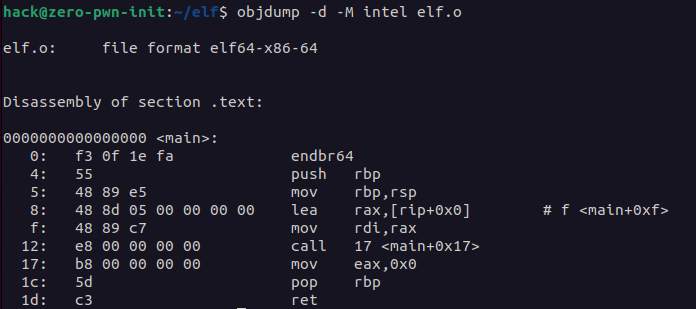

Let’s now delve into practical implementation by constructing a customized program coupled with our proprietary Shared Library.

The initial phase entails crafting the essential headers, referred to as shared_elf.h, for our libraries. Within this header, we will define a singular function, named shared_ELF.

1

2

3

4

5

6

#ifndef shared_ELF_h__

#define shared_ELF_h__

extern void shared_ELF(void);

#endif // shared_ELF_h__

The second step is to create the shared_elf.c which contains the implementation of that function.

1

2

3

4

5

#include <stdio.h>

void shared_ELF(void){

puts("Ups you unlock the secret....");

}

The final step is to use our program (elf.c) from the previous exemple to print “Secret of the ELF Binary!” and adding the function shared_ELF().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#include <stdio.h>

#include "shared_elf.h"

int main(){

printf("Secret of the ELF Binary!\n");;

shared_ELF();

return 0;

}

We need to compile our library source code into Position-Independent Code.

Note: Creating shared libraries or executables that must be loaded at various memory locations in a process’s address space requires the use of a programming method known as position-independent code (PIC). Due to elements like address space layout randomization (ASLR) and the shared library mechanism, PIC is a crucial idea for contemporary computers.

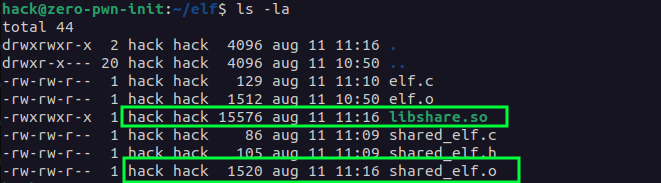

For now we have 3 important files:

Compile our library source code:

1

gcc -c -Wall -Werror -fpic shared_elf.c

Now we need to actually turn this Object File shared_elf.o into a shared library. We will call it libshare.so:

1

gcc -shared -o libshare.so shared_elf.o

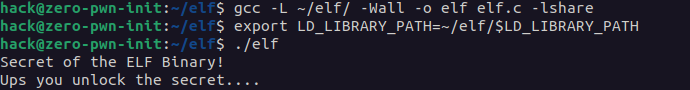

We build our elf.c with a shared library, libshare.so, and link them together. To accomplish that, we must inform the GCC compiler of the location of the Shared Library.

1

gcc -L ~/elf/ -Wall -o elf elf.c -lshare

Also to avoid errors when we run a program like this (./elf: error while loading shared libraries: libshare.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory). We need to export the path where the LD_LYBRARY is because our loader doesn’t know where the .so file is.

1

export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=~/elf/$LD_LIBRARY_PATH

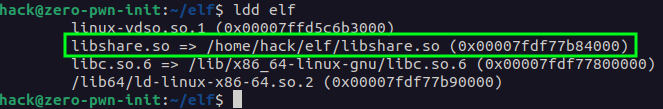

We can see the Shared Library is loaded successfully, but we can see all the Shared Object dependencies the program loads using the ldd tool.

Structure of an ELF binary file.

An ELF file has a “file header” which describes the file in general and then has pointers to each of the individual sections that make up the file. The ELF header for x64 architectures looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

typedef struct {

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT];

Elf64_Half e_type;

Elf64_Half e_machine;

Elf64_Word e_version;

Elf64_Addr e_entry;

Elf64_Off e_phoff;

Elf64_Off e_shoff;

Elf64_Word e_flags;

Elf64_Half e_ehsize;

Elf64_Half e_phentsize;

Elf64_Half e_phnum;

Elf64_Half e_shentsize;

Elf64_Half e_shnum;

Elf64_Half e_shstrndx;

} Elf64_Ehdr;

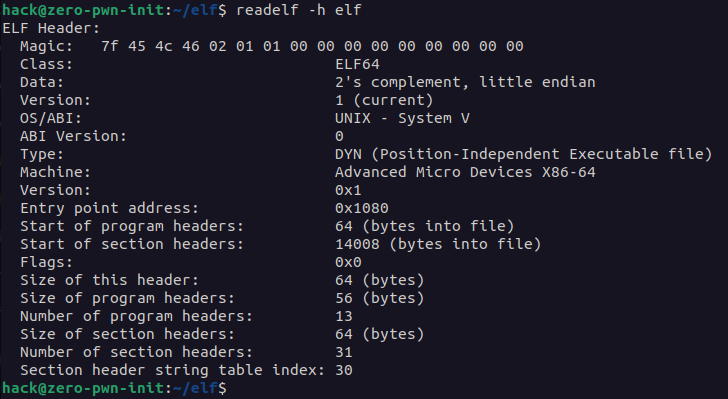

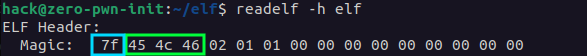

Another information can be obtain using the readelf tool (readelf is a program which help as to show the header in the readable form):

The e_ident[EI_NIDENT] is the first thing in any ELF file, and it always begins with a few “magic” bytes. The first byte is 0x7F, and the following three bytes are “ELF”. You can see this for yourself by inspecting an ELF binary with something like the hexdump/readelf command.

If you take a look at the code and the readelf section we can see a similar pattern:

| Field | Description | Correspondence |

|---|---|---|

| e_type | Type of file | Corresponds with file type (readelf section Class) |

| e_machine | Type of system architecture | Corresponds with system type (readelf OS/ABI section) |

| e_version | Original version of ELF file | Corresponds with version (readelf Version section) |

| e_entry | Memory address of entry point | Entry point of process execution (readelf Entry Point Section) |

| e_phoff | Offset to the start of program header table | Start of the program header table |

| e_shoff | Offset to the start of section header table | Start of the section table |

| e_flags | Flags specific to the architecture | Architecture-specific flags |

| e_ehsize | Size of the ELF header | Header size based on architecture |

| e_phentsize | Size of a program header table entry | Size of a program header entry |

| e_phnum | Number of entries in the program header table | Number of program header entries |

| e_shentsize | Size of a section header table entry | Size of a section header entry |

| e_shnum | Number of entries in the section header table | Number of section header entries |

| e_shstrndx | Index of the entry containing section names in the section header table | Index of section containing section names |

The header structures contain another two sections:

- Program headers table that segment describes how to create a process and memory image on the runtime execution.

- Section headers table defines all the sections in the file and is used for linking and relocation.

Graphic representation of the ELF Structures format:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| ELF Header | Header information about the ELF file |

| Program Header Table | Describes program segments |

| .text | Executable instructions |

| .rodata | Read-only data |

| ……. | Other sections (if applicable) |

| .data | Initialized data |

| Section Header Table | Describes sections |

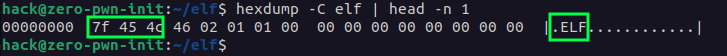

Let’s create our own basic script that displays the ELF header format. The logic of the script is simple, we can use the pyelftools to get all the information needed about the ELF format. First, we need to create a function that is able to parse/read hex format. Another function “byte2int()” return the value of the b variable. Now the main function is to open the file in bytes format and print all the headers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

import sys

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from elftools.elf.descriptions import (

describe_ei_class, describe_ei_data, describe_ei_version,

describe_ei_osabi, describe_e_type, describe_e_machine,

describe_e_version_numeric)

def _format_hex(elffile, addr, fieldsize=None, fullhex=False, lead0x=True, alternate=False):

if alternate:

if addr == 0:

lead0x = False

else:

lead0x = True

fieldsize -= 2

s = '0x' if lead0x else ''

if fullhex:

fieldsize = 8 if elffile.elfclass == 32 else 16

if fieldsize is None:

field = '%x'

else:

field = '%' + '0%sx' % fieldsize

return s + field % addr

def byte2int(b): return b

if __name__ == '__main__':

file = open("./elf", 'rb')

elffile = ELFFile(file)

print('ELF Header:')

print(' Magic: ')

print(' '.join('%2.2x' % byte2int(b)

for b in elffile.e_ident_raw))

print(' ')

header = elffile.header

e_ident = header['e_ident']

print(' Class: %s' %

describe_ei_class(e_ident['EI_CLASS']))

print(' Data: %s' %

describe_ei_data(e_ident['EI_DATA']))

print(' Version: %s' %

describe_ei_version(e_ident['EI_VERSION']))

print(' OS/ABI: %s' %

describe_ei_osabi(e_ident['EI_OSABI']))

print(' ABI Version: %d' %

e_ident['EI_ABIVERSION'])

print(' Type: %s' %

describe_e_type(header['e_type']))

print(' Machine: %s' %

describe_e_machine(header['e_machine']))

print(' Version: %s' %

describe_e_version_numeric(header['e_version']))

print(' Entry point address: %s' %

_format_hex(elffile, header['e_entry']))

print(' Start of program headers: %s' %

header['e_phoff'])

print(' (bytes into self)')

Program Headers Table

An ELF file is made up of zero or more segments that describe how to create a process or memory image for execution at runtime. When the kernel detects these segments, it uses the mmap(2) system call to map them into virtual address space. To put it another way, it converts predefined instructions into a memory image. These program headers are required if your ELF file is a normal binary. Otherwise, it will simply not run. It constructs a process from these headers and the underlying data structure. This procedure is similar to that of shared libraries.

Note: mmap syscall it’s used to create a new mapping in the virtual address space of the calling process. The starting address for the new mapping is specified in addr. The length argument specifies the length of the mapping (which must be greater than 0).

The elements of this structure are:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef struct {

Elf64_Word p_type;

Elf64_Word p_flags;

Elf64_Off p_offset;

Elf64_Addr p_vaddr;

Elf64_Addr p_paddr;

Elf64_Xword p_filesz;

Elf64_Xword p_memsz;

Elf64_Xword p_align;

} Elf64_Phdr;

A brief and simplified guide to understanding the meaning of each section:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| p_type | Describes how to interpret the array element’s information. |

| p_offset | Offset from the beginning of the file at which the first byte of the segment resides. |

| p_vaddr | Virtual address at which the first byte of the segment resides in memory. |

| p_paddr | Physical address for systems in which physical addressing is relevant. |

| p_filesz | Number of bytes in the file image of the segment, which can be zero. |

| p_memsz | Number of bytes in the memory image of the segment, which can be zero. |

| p_flags | Flags relevant to the segment. |

| p_align | Loadable process segments must have congruent values for p_vaddr and p_offset, modulo the page size. |

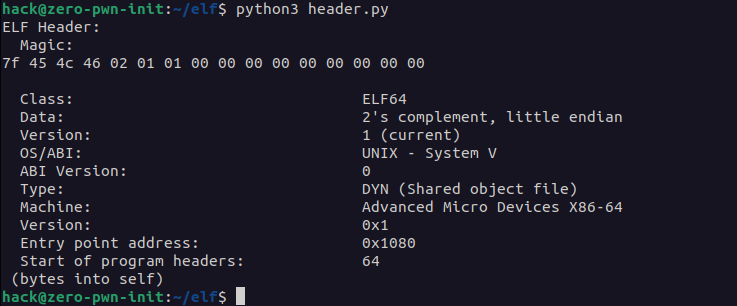

Another piece of information about the Program Header Table can be obtained using the readelf tool:

Green color represents the Header Table, yellow color represents the structure of the header and red color represents the permission of the section. As you can see we have in column type some notation:

| Segment Type | Description |

|---|---|

| pt_PHDR | Specifies the location and size of the program header table, both in the file and in the program’s memory image. This segment type can only appear once in a file. Furthermore, it can occur only if the program header table is part of the program’s memory image. If present, this type must come before any loadable segment entry. |

| pt_INTERP | The location and size of a null-terminated path name to use as an interpreter. This segment type is required for dynamic executable files and may also appear in shared objects. It can only appear once in a file. If present, this type must come before any loadable segment entry. |

| pt_LOAD | Describes a loadable segment using p_filesz and p_memsz. The bytes from the file are assigned to the start of the memory segment. If the memory size (p_memsz) of the segment is greater than the file size (p_filesz), the extra bytes are defined to hold the value 0 and to follow the segment’s initialized area. The file size cannot be greater than the available memory. Loadable segment entries in the program header table are sorted on the p vaddr member and appear in ascending order. |

| pt_DYNAMIC | Specifies dynamic linking information. |

| pt_NOTE | Specifies the location and size of auxiliary information. |

| GNU_EH_FRAME | This is a sorted queue that the GNU C compiler uses (gcc). It keeps track of exception handlers. So, if something goes wrong, it can use this area to deal with it properly. |

| GNU_STACK | This header contains stack information. The stack is a buffer or scratch location where items such as local variables are stored. LIFO (Last In, First Out) will cause this, similar to stacking boxes on top of each other. A block is reserved when a process function is started. |

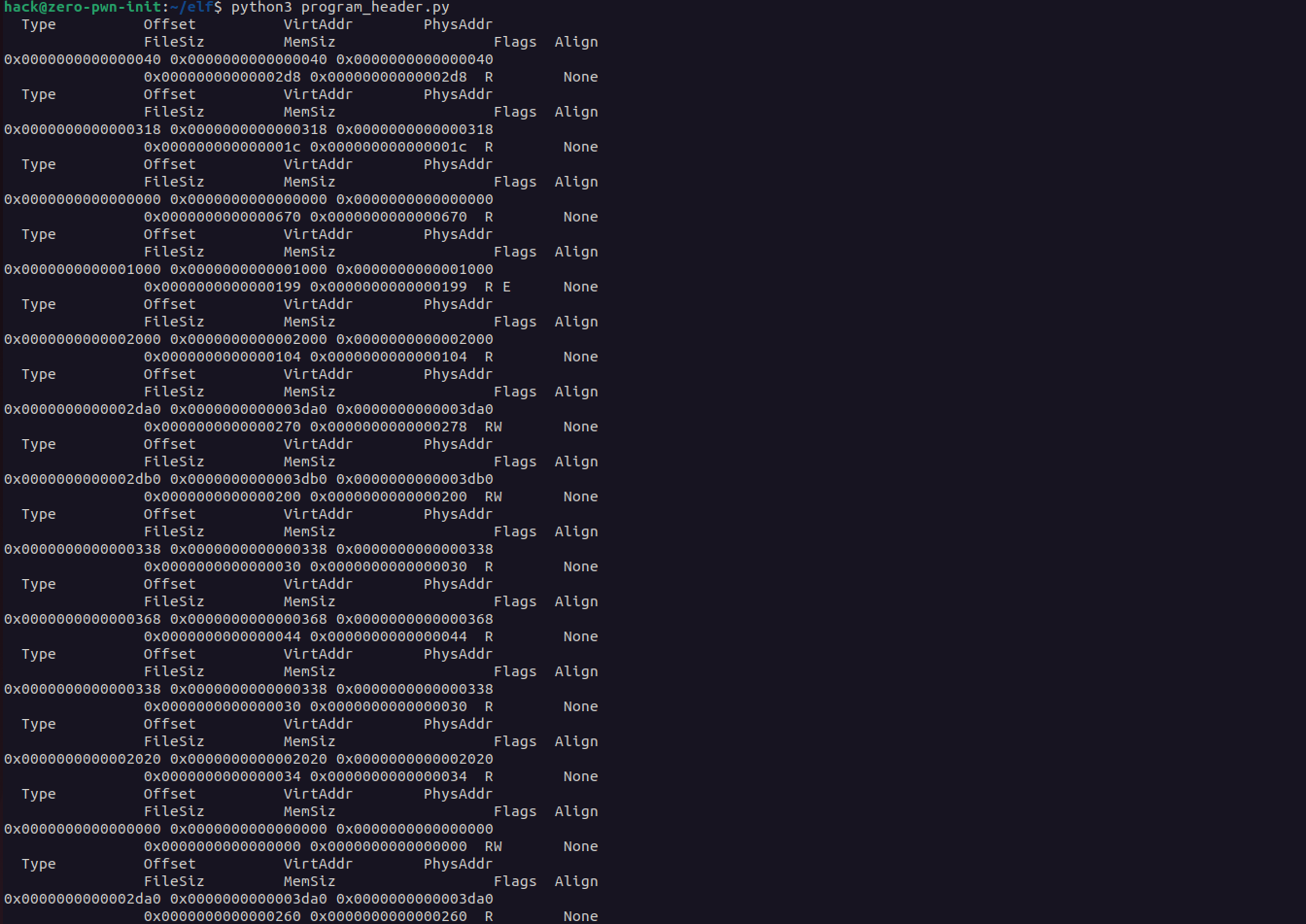

Let’s create our own basic script that displays the ELF Program header table. The logic of the script is simple, we can use the pyelftools to get all the information needed about the ELF format. First, we need to create a function that is able to parse/read hex format. Now the main function is to open the file in bytes format but is not enough just to open the binary, we need to parse the segment section, to do that we use iteration to read all the program headers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

import sys

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from elftools.elf.segments import Segment

from elftools.elf.descriptions import describe_p_flags

def _format_hex(elffile, addr, fieldsize=None, fullhex=False, lead0x=True, alternate=False):

if alternate:

if addr == 0:

lead0x = False

else:

lead0x = True

fieldsize -= 2

s = '0x' if lead0x else ''

if fullhex:

fieldsize = 8 if elffile.elfclass == 32 else 16

if fieldsize is None:

field = '%x'

else:

field = '%' + '0%sx' % fieldsize

return s + field % addr

if __name__ == '__main__':

file = open("./elf", 'rb')

elffile = ELFFile(file)

for segment in elffile.iter_segments():

print(' Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr')

print(' FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align')

print('%s %s %s' % (

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_offset'], fullhex=True),

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_vaddr'], fullhex=True),

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_paddr'], fullhex=True)))

print(' %s %s %-3s %s' % (

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_filesz'], fullhex=True),

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_memsz'], fullhex=True),

describe_p_flags(segment['p_flags']),

_format_hex(elffile,segment['p_align'], lead0x=False)))

Segment Headers Table

The Section Header Table is an array with each entry pointing to one of the ELF file’s sections. In this section is all information needed for linking a target Object File in order to build a working executable.

Note: It’s important to highlight that section headers are needed on link-time but they are not needed on runtime.

The elements of this structure are:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

typedef struct {

Elf64_Word sh_name;

Elf64_Word sh_type;

Elf64_Word sh_flags;

Elf64_Addr sh_addr;

Elf64_Off sh_offset;

Elf64_Word sh_size;

Elf64_Word sh_link;

Elf64_Word sh_info;

Elf64_Word sh_addralign;

Elf64_Word sh_entsize;

} Elf64_Shdr;

A brief and simplified guide to understanding the meaning of each section:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| sh_name | The name of the section. Its value is an index into the section header string table section giving the location of a null-terminated string. |

| sh_type | Categorizes the section’s contents and semantics. |

| sh_flags | Describes miscellaneous attributes. |

| sh_addr | If the section is to appear in the memory image of a process, this member gives the address at which the section’s first byte should reside. Otherwise, the member contains 0. |

| sh_offset | The byte offset from the beginning of the file to the first byte in the section. |

| sh_link | A section header table index link, whose interpretation depends on the section type. |

| sh_info | Extra information, whose interpretation depends on the section type. |

| sh_addralign | Some sections have address alignment constraints. For example, if a section holds a double word, the system must ensure double-word alignment for the entire section. That is, the value of sh_addr must be congruent to 0, modulo the value of sh_addralign. Currently, only 0 and positive integral powers of two are allowed. Values 0 and 1 mean the section has no alignment constraints. |

| sh_entsize | Some sections hold a table of fixed-size entries, such as a symbol table. For such a section, this member gives the size in bytes of each entry. The member contains 0 if the section does not hold a table of fixed-size entries. |

Another piece of information about the Segment Header Table can be obtained using the readelf` tool:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 0000000000000318 00000318

000000000000001c 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.gnu.pr[...] NOTE 0000000000000338 00000338

0000000000000030 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[ 3] .note.gnu.bu[...] NOTE 0000000000000368 00000368

0000000000000024 0000000000000000 A 0 0 4

[ 4] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 000000000000038c 0000038c

0000000000000020 0000000000000000 A 0 0 4

[ 5] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 00000000000003b0 000003b0

0000000000000024 0000000000000000 A 6 0 8

[ 6] .dynsym DYNSYM 00000000000003d8 000003d8

00000000000000c0 0000000000000018 A 7 1 8

[ 7] .dynstr STRTAB 0000000000000498 00000498

00000000000000a4 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 8] .gnu.version VERSYM 000000000000053c 0000053c

0000000000000010 0000000000000002 A 6 0 2

[ 9] .gnu.version_r VERNEED 0000000000000550 00000550

0000000000000030 0000000000000000 A 7 1 8

.........

[20] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000002058 00002058

00000000000000ac 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[21] .init_array INIT_ARRAY 0000000000003da0 00002da0

0000000000000008 0000000000000008 WA 0 0 8

[22] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0000000000003da8 00002da8

0000000000000008 0000000000000008 WA 0 0 8

[23] .dynamic DYNAMIC 0000000000003db0 00002db0

0000000000000200 0000000000000010 WA 7 0 8

[24] .got PROGBITS 0000000000003fb0 00002fb0

0000000000000050 0000000000000008 WA 0 0 8

[25] .data PROGBITS 0000000000004000 00003000

0000000000000010 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 8

[26] .bss NOBITS 0000000000004010 00003010

0000000000000008 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[27] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00003010

000000000000002b 0000000000000001 MS 0 0 1

[28] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 00003040

0000000000000378 0000000000000018 29 18 8

[29] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 000033b8

00000000000001e4 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[30] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 0000359c

000000000000011a 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

D (mbind), l (large), p (processor specific)

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| .bss | This section holds uninitialized data that contributes to the program’s memory image. By definition, the system initializes the data with zeros when the program begins to run. |

| .comment | This section holds version control information. |

| .data, .data1 | These sections hold initialized data that contribute to the program’s memory image. |

| .debug | This section holds information for symbolic debugging. The contents are unspecified. |

| .dynamic | This section holds dynamic linking information. |

| .dynstr | This section holds strings needed for dynamic linking, most commonly the strings that represent symbol names. |

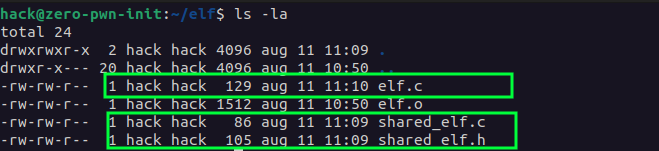

| .dynsym | This section holds the dynamic linking symbol table. |

| .fini | This section holds executable instructions that contribute to the process termination code. |

| .fini_array | This section holds an array of function pointers that contributes to termination for the executable/shared object. |

| .got | This section holds the global offset table. |

| .hash | This section holds a symbol hash table. |

| .init | This section holds executable instructions that contribute to the process initialization code. |

| .init_array | This section holds an array of function pointers for initialization of executable/shared object. |

| .interp | This section holds the path name of a program interpreter. |

| .note | This section holds information in a specified format. |

| .plt | This section holds the procedure linkage table. |

| .rela.dyn, .rela.plt | These sections hold relocation information. |

| .rodata, .rodata1 | These sections hold read-only data that contributes to a non-writable segment in the process image. |

| .shstrtab | This section holds section names. |

| .strtab | This section holds strings, often symbol names. |

| .symtab | This section holds a symbol table. |

| .text | This section holds executable instructions of a program. |

Let’s create our own basic script that displays the ELF Segment header table. The logic of the script is simple, we can use the pyelftools to get all the information needed about the ELF format. First, we need to create a function that is able to parse/read hex format. Now the main function is to open the file in bytes format and just read the array section which contains the information.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

import sys

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from elftools.elf.descriptions import (describe_sh_flags,describe_sh_type)

def _format_hex(elffile, addr, fieldsize=None, fullhex=False, lead0x=True,

alternate=False):

if alternate:

if addr == 0:

lead0x = False

else:

lead0x = True

fieldsize -= 2

s = '0x' if lead0x else ''

if fullhex:

fieldsize = 8 if elffile.elfclass == 32 else 16

if fieldsize is None:

field = '%x'

else:

field = '%' + '0%sx' % fieldsize

return s + field % addr

if __name__ == '__main__':

file = open("./elf", 'rb')

elffile = ELFFile(file)

elfheader = elffile.header

show_heading = True

if show_heading:

print('There are %s section headers, starting at offset %s' % (

elfheader['e_shnum'],_format_hex(elffile,elfheader['e_shoff'])))

print('\nSection Header%s:' % (

's' if elffile.num_sections() > 1 else ''))

print(' [Nr] Name Type Address Offset')

print(' Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align')

for nsec, section in enumerate(elffile.iter_sections()):

print(' [%2u] %-17.17s %-15.15s ' % (

nsec, section.name, describe_sh_type(section['sh_type'])))

print(' %s %s' % (

_format_hex(elffile,section['sh_addr'], fullhex=True, lead0x=False),

_format_hex(elffile,section['sh_offset'],

fieldsize=16 if section['sh_offset'] > 0xffffffff else 8,

lead0x=False)))

print(' %s %s %3s %2s %3s %s' % (

_format_hex(elffile,section['sh_size'], fullhex=True, lead0x=False),

_format_hex(elffile,section['sh_entsize'], fullhex=True, lead0x=False),

describe_sh_flags(section['sh_flags']),

section['sh_link'], section['sh_info'],

section['sh_addralign']))

print('Key to Flags:')

print(' W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge),'

' S (strings), I (info),')

print(' L (link order), O (extra OS processing required),'

' G (group), T (TLS),')

print(' C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific),'

' E (exclude),')

In conclusion, a thorough grasp of the structure and organization of executable and object files is provided by the in-depth examination of ELF file internals. The many sections, headers, and their respective functions in determining the properties of an ELF file have been investigated, revealing light on how the operating system loads, runs, and manages applications.

You can use the following resources for more research and investigation to go deeper into this subject and widen your perspectives. With the help of these materials, you may improve your understanding of and ability to work with ELF files, binary formats, and system internals.

Please refer to the following website for additional analysis.

Reference

https://www.caichinger.com/elf.html

https://refspecs.linuxfoundation.org/LSB_1.2.0/gLSB/specialsections.html

https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E19683-01/816-1386/chapter6-94076/index.html

https://www.ics.uci.edu/~aburtsev/238P/hw/hw3-elf/hw3-elf.html

https://www.intezer.com/blog/malware-analysis/executable-and-linkable-format-101-part-3-relocations/

http://refspecs.linux-foundation.org/LSB_4.0.0/LSB-Core-generic/LSB-Core-generic/sections.html

https://www.intezer.com/blog/research/executable-linkable-format-101-part1-sections-segments/

https://linux-audit.com/elf-binaries-on-linux-understanding-and-analysis/

https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E19683-01/816-1386/6m7qcoblk/index.html#chapter6-20567