How to create your own shellcode Part I

Hello everyone. Today, we’ll talk about what shellcode is and how to make it.

How does Shellcode work?

In hacking, a shellcode is a small piece of code that is used as the payload when a software flaw is exploited. It is called “shellcode” because it usually starts a command shell from which the attacker can handle the compromised machine. However, any piece of code that does the same thing can be called “shellcode.” Some people think that the name “shellcode” isn’t good enough because a payload’s purpose isn’t just to start a shell. But most people don’t like the alternatives that have been tried. Machine code is often used to write shellcode. Machine code is often used to write shellcode.

What should you know before you begin?

You need to know x86/x64 assembly, C, and the Linux and Windows operating platforms.

On the x64 OS, General Purpose Registers:

| Register | Description |

|---|---|

| rax | Accumulator |

| rbx | Base |

| rcx | Counter |

| rdx | Data |

| rsi | Source Index |

| rdi | Destination Index |

| rbp | Base Pointer |

| rsp | Stack Pointer |

| r8 | General Purpose Register 8 |

| r9 | General Purpose Register 9 |

| r10 | General Purpose Register 10 |

| r11 | General Purpose Register 11 |

| r12 | General Purpose Register 12 |

| r13 | General Purpose Register 13 |

| r14 | General Purpose Register 14 |

| r15 | General Purpose Register 15 |

Registers for general use on the x32 platform:

| Register | Description |

|---|---|

| eax | Accumulator |

| ebx | Base |

| ecx | Counter |

| edx | Data |

| esi | Source Index |

| edi | Destination Index |

| ebp | Base Pointer |

| esp | Stack Pointer |

| r8d | General Purpose Register 8 |

| r9d | General Purpose Register 9 |

| r10d | General Purpose Register 10 |

| r11d | General Purpose Register 11 |

| r12d | General Purpose Register 12 |

| r13d | General Purpose Register 13 |

| r14d | General Purpose Register 14 |

| r15d | General Purpose Register 15 |

Get the x16 bits at the top of the GPRs.

| Register | Description |

|---|---|

| ax | Accumulator |

| bx | Base |

| cx | Counter |

| dx | Data |

| si | Source Index |

| di | Destination Index |

| bp | Base Pointer |

| sp | Stack Pointer |

| r8w | General Purpose Register 8 |

| r9w | General Purpose Register 9 |

| r10w | General Purpose Register 10 |

| r11w | General Purpose Register 11 |

| r12w | General Purpose Register 12 |

| r13w | General Purpose Register 13 |

| r14w | General Purpose Register 14 |

| r15w | General Purpose Register 15 |

Access the GPRs’ lower x8 bits.

| Register | Description |

|---|---|

| al | Accumulator Low |

| bl | Base Low |

| cl | Counter Low |

| dl | Data Low |

| sil | Source Index Low |

| dil | Destination Index Low |

| bpl | Base Pointer Low |

| spl | Stack Pointer Low |

| r8b | General Purpose Register 8 |

| r9b | General Purpose Register 9 |

| r10b | General Purpose Register 10 |

| r11b | General Purpose Register 11 |

| r12b | General Purpose Register 12 |

| r13b | General Purpose Register 13 |

| r14b | General Purpose Register 14 |

| r15b | General Purpose Register 15 |

When making Linux syscalls, ESI and EDI are used.

Using XOR EAX, EAX to clear a register is a great way to avoid the dangerous NULL bit!

In Windows, all function inputs are put on the stack based on how the function is called.

If you want to learn more about syscall, click on this link: (syscalls).

Example of Shellcode!

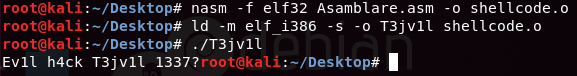

First, we’ll write a small program in assembly code that will show Ev1l T3jv1l h4ck 1337?

You are probably using an operating system with a random stack and address space, and there may be a security feature that stops you from running code on the stack. Not every Linux-based operating system is the same, so I’ll show you a method for Ubuntu that should be easy to adapt.

echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/exec-shield (to turn it off)

echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space (to turn it off)

echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/exec-shield (turn on)

echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space [[make it work]]

First, we use the touch command to make a file with the name *.asm and then we use the nano editor to write code. This is an example for 32 bit! You need to put in:

1

sudo apt-get install lib32z1 lib32ncurses5

Assembly code for our shellcode:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

global _start

section .text

_start:

jmp message

proc:

xor eax, eax

mov al, 0x04

xor ebx, ebx

mov bl, 0x01

pop ecx

xor edx, edx

mov dl, 0x16

int 0x80

xor eax, eax

mov al, 0x01

xor ebx, ebx

mov bl, 0x01

int 0x80

message:

call proc

msg db "Ev1l h4ck T3jv1l 1337?"

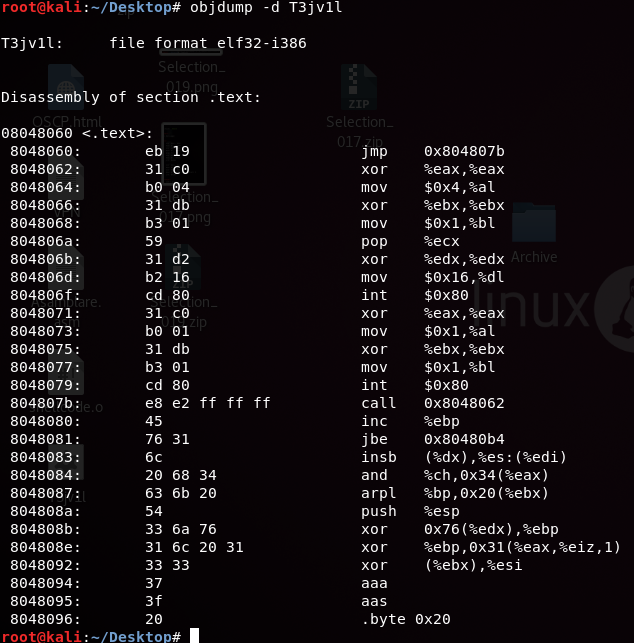

The global _start directive specifies that the symbol _start is globally accessible. The section .text directive indicates that the following instructions belong to the .text section, which typically contains executable code. _start is the entry point of the program. It is the first instruction executed when the program starts. In this case, it jumps to the message label.

The proc is a label that defines a procedure or function. The first block of instructions sets up a system call to write to the standard output.

Here’s a breakdown of the instructions:

xor eax, eaxsets eax (the register for the system call number) to zero.mov al, 0x04moves the value 0x04 (system call number for write) into the lower 8 bits of eax.xor ebx, ebxsets ebx (the register for the file descriptor) to zero.mov bl, 0x01moves the value 0x01 (file descriptor for standard output) into the lower 8 bits of ebx.pop ecxretrieves the value from the top of the stack and stores it in ecx. This is likely used to obtain the address of the msg string.xor edx, edxsets edx (the register for the data length) to zero.mov dl, 0x16moves the value 0x16 (length of the string) into the lower 8 bits of edx.int 0x80triggers a software interrupt, invoking the system call.

The second block of instructions sets up a system call to exit the program. Here’s a breakdown of the instructions:

xor eax, eaxsets eax (the register for the system call number) to zero.mov al, 0x01moves the value 0x01 (system call number for exit) into the lower 8 bits of eax.xor ebx, ebxsets ebx (the register for the exit status) to zero.mov bl, 0x01moves the value 0x01 (exit status) into the lower 8 bits of ebx.int 0x80triggers a software interrupt, invoking the system call to exit the program.messageis a label that marks the start of the msg string.call proccalls the proc procedure, executing the code inside it.msg db "Ev1l h4ck T3jv1l 1337?"defines a string named msg with the value “Ev1l h4ck T3jv1l 1337?”.

This time, we need to use the next command to compile this code:

1

2

nasm -f elf32 Asamblare.asm -o shellcode.o

ld -m elf_i386 -s -o T3jv1l shellcode.o

We can see the machine code called opcode to see how the program operate:

1

objdump -d T3jv1l

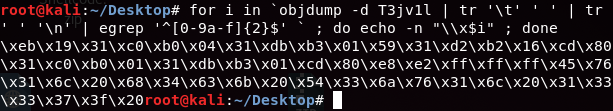

To extract all the opcode we can use next command:

1

for i in `objdump -d T3jv1l | tr '\t' ' ' | tr ' ' '\n' | egrep '^[0-9a-f]{2}$' ` ; do echo -n "\\x$i" ; done

Ok, let’s make a small program in the computer language C to see if this shellcode will run.

This is how the C code will look:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#include <"stdio.h">

char shellcode[] ="\xeb\x19\x31\xc0\xb0\x04\x31\xdb\xb3\x01\x59\x31\xd2\xb2\x16\xcd\x80\x31\xc0\xb0\x01\x31\xdb\xb3\x01\xcd\x80\xe8\xe2\xff\xff\xff\x45\x76\x31\x6c\x20\x68\x34\x63\x6b\x20\x54\x33\x6a\x76\x31\x6c\x20\x31\x33\x33\x37\x3f\x20";

int main(int argc, char **argv) int main(int argc, char **argv){

int *ret;

ret = (int *)&ret + 2;

(*ret) = (int)shellcode;

}

Okay, we know that char shellcode[] saves the opcodes for our shellcode in hexadecimal format. Then, the main method does some kind of trick to run this shellcode. If we run the program after building it as an ELF32 binary with the -z execstack flag set, we get our shell.

First, it uses the main() method to set up a variable of type int *ret, which is a pointer of type int. This value will be right after the saved ebp register in the main’s stack frame.

Because our ret variable is right after the saved ebp register, the return address that was saved before calling the main() method will be found before the saved ebp register.

So, it looks like we can use our ret pointer to point to the saved return address and replace it with the address of our shellcode.

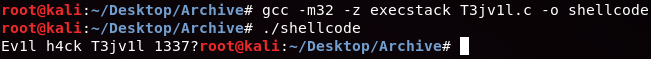

Now let’s see if the C program works by compiling it.

1

gcc -m32 -z execstack T3jv1l.c -o shellcode

BONUS!!!

I made my own extract opcode tool in Python, which you can find at https://github.com/T3jv1l/Sh3llshock.

If you look, you’ll see that it’s the same shellcode as the one above, and this tool makes it just as easy to extract.

This might not be the best example of Shellcode, but it might help you understand how they are made and how they can be run. We appreciate your time. (Please excuse my English, I’m not a native speaker.)

Reference

http://www.vividmachines.com/shellcode/shellcode.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shellcode

https://www.amazon.com/Shellcoders-Handbook-Discovering-Exploiting-Security/dp/047008023X

https://www.exploit-db.com/building-your-own-ud-shellcodes-part-1.pdf